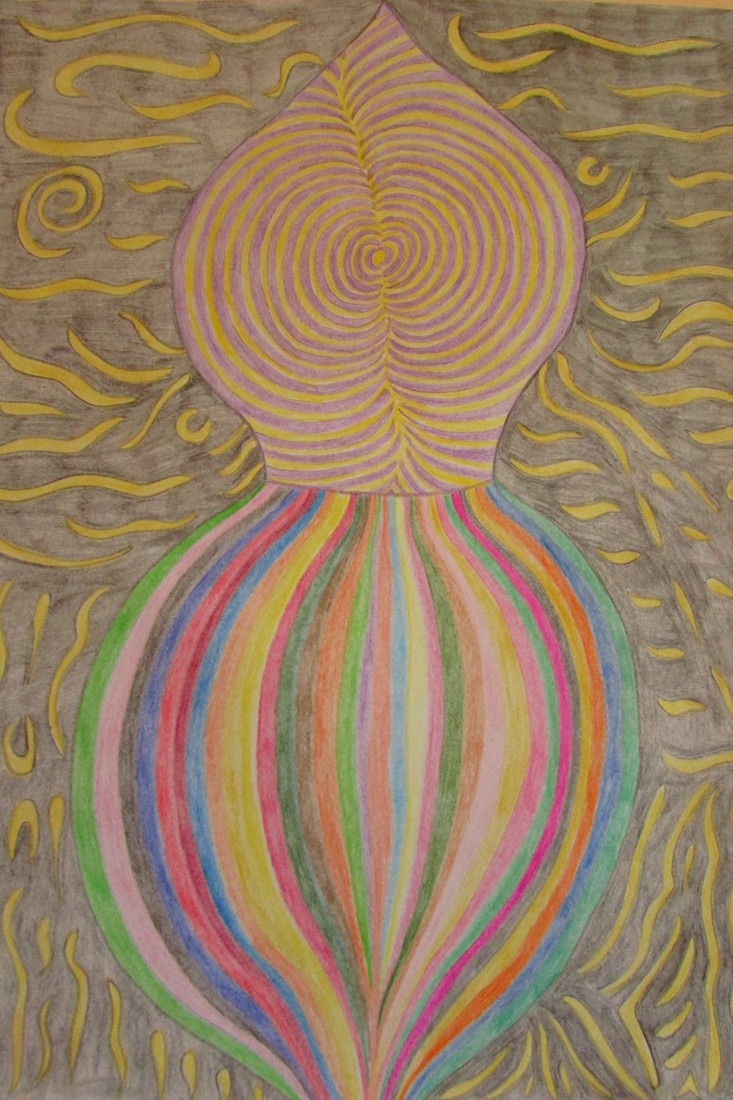

The Tree Outside my Bedroom Window, Dartington The Tree Outside my Bedroom Window, Dartington For my MA Ecology and Spirituality, I was given the assignment of writing a reflective journal and critical commentary on a subject of my choice. I chose the question what do people really mean when they say 'I speak to trees'? I am very pleased with how it turned out, so thought I could share it with you. I have taken the references out, but please do ask if you want to know where the quotes come from. At the end is an intuitive drawing of my own, given by the tree outside my window at Dartington. What do people really mean when they say ''I speak to trees''? Excerpts from my Journal: January-February 2017. Jenny said 'Choose a room on this side of the building, then you can see the beautiful tree.' During the welcome party I was given a piece of paper, a wish, which said the words: 'May you grow to know a tree as an old friend’. And so I began to wonder how I would begin speaking to the tree outside my window. Andy sang and played his lyre to the ancient Yew tree, knowing that the tree could hear him. One night we went to watch Pagan Morris Dancing, with a Wassailing ceremony afterwards. We sang to the apple trees and put cider soaked bread on the branches. These traditional folk festivities are for the apple trees to know that they are celebrated and loved, so they will wake up and bear fruit when the season comes. Steph said she had a connection with a Yew tree, close by to the ancient one. We went to visit, and Steph told me that this was the masculine to the ancient feminine Yew that everyone visits. She said when she walked past him it was like a pull she felt in her heart. An intuition. A knowing. And the messages come as feelings. This one told her that it is the masculine that needs healing in the world, more than the feminine. Nicola said 'I was walking one day, and I heard a voice calling out my name.' She looked around and no one was there: she realised a plant was talking to her. I asked her how to talk to trees, and she told me trees are much slower than us, so we must give them time to speak. If a person walks through the forest, everything stops. We must be still and let the forest re-balance itself. Sit under the tree, introduce yourself, and then just write, or draw, whatever comes to you. Stephan said 'touch the trees and plants as if they can feel your touch.' And the daffodils purred when I stroked them. And the tree enjoyed my massage, especially in the knots. And I stood and looked at the trees, in awe, and they could see me and were in awe of me too. Pat said 'I choose rocks for my sweat lodge by asking them politely and with humility to come with me. These are ancient rocks. One rock may have been having a conversation of infinite wisdom for thousands of years with its neighbour. So I reach out to the ancient ones, and ask which of them are happy to help me and my relatives on our humble, human journey. And as I am walking around, some catch my eye, or I get a feeling that they are saying 'yes, I will come with you'. I thank them all for allowing their family member to come with me.' Jenny watches, Andy sings, Steph knows, Nicola hears, Stephan touches, and Pat gives and receives. I have connected with non-human beings before, though not with trees. I am a crystal artist, I can meditate with a crystal, and draw the images and colours that come to me. And so I decide to take Nicola's advice, and I do the same with the tree outside my window. I go to it, introduce myself, wait patiently. It does not take so long before the images come. I collect the images, keep them in my mind, draw them. As I am drawing I realise a simple truth: this is not what I saw. I am so limited by my memory of what I saw, by my terrible artwork, by the medium of my expression: the paper and pencils. What I saw was so alive, vibrant, pulsating, living, that I could not possibly express it in words, or in art. What I drew on my paper was the closest approximation of what I saw, but it does not even come close. And so I must conclude that all the watching, singing, soul-connections, hearing, touching, giving and receiving that all the people I have spoken to have described to me: None of it comes close to the persons' actual experience. And so, I will never know what people really mean when they say 'I speak to trees.' Critical Commentary. In this reflective journal I touch on the subject of animism. Animism is a type of religion that engages a wide community of living beings, with whom humans share the world. Earth holds a wide range of persons, only some of whom are human. 'All that exists lives' and 'all that lives is holy'. Animism could be the first and only universal religion. Quinn believes so, as animism has existed for tens of thousands of years, and is still in place now with indigenous peoples. The word animism itself comes from the Latin word for soul or spirit and views the world as 'a sacred place, and humanity belongs in such a world': humans are as sacred as everything else. Harvey tells us how animists assert that 'it is possible to ''speak with'' and ''listen to'' trees...'. To some in the West this may seem a little far-fetched. But I love Campbell’s explanation of animism. He says that the tag of animism has been so caught up in ideas of classifying religion that the point has been lost. It shows Western separation from the idea: 'behind the term lurked the grounding idea that whereas we [the West] know what is alive and what is not, they [indigenous peoples] don't'. There are two notions of what animism is: one is that indigenous peoples think that everything around them is alive, and the other is that all things have a soul or spirit that makes them alive. Campbell doesn't believe that 'calling one or the other 'animism' marks any great divide between us and them', because we (the West) already take it for granted that animals are alive. So begs the question: what is the difference between talking to my cat, and talking to the tree outside my window? In my journal, Steph spoke to and listened to the Yew tree. She received a message: that the masculine energy of the world needs to be healed, just as much as, if not more than, the feminine. Maybe it was her specifically who was supposed to receive this message, or perhaps she was just open enough to hear what the tree had been saying for many years. Harvey says 'the ''speaking with'' and ''listening to'' trees may not be a pursuit of information, though some Pagans assert trees are willing to communicate in some way things that we would otherwise be unaware of'. So while Steph was not consciously looking for information, the tree was 'willing to communicate' something that she 'would otherwise be unaware of.’ Harvey's italics of how a tree communicates in 'some way', suggests there is no definitive way of communicating with a tree: Steph experienced the communication through her heart and intuition, and others have different experiences. In the language of the Native American Ojibwe people, words are grammatically animistic: different grammar is used depending on whether an object is alive or not. It makes sense, as people can speak with animate objects, but can only speak about inanimate ones. For example, anthropologist Hallowell asks an Ojibwe man whether all rocks are alive: he replies that not all of them are, and advises how to know. If we can recognise a rock’s life, agency, will, or intellect, we can engage in social reciprocity with that rock-being, just as with a human-being. Hallowell observes: ‘relationships are both moral and reciprocal, not only among humans but between humans and "other-than-human persons" as a necessary, vital, and everyday part of life’. In my journal I mention Native American Pat McGabe relating to rocks by asking permission to take some for her sweat lodge. In a similar way, trees can teach us 'the virtue of respect, the pleasure of intimacy and the vital importance of eco-responsibility'. This is exactly what Pat indicates: respecting rocks as beings in their own right; taking pleasure in creating an intimate relationship with them; and eco-responsibility through asking permission before taking, being humble and recognising that the human is entering the world of the rock, not the other way around. If rocks have their own lives, communities, families and conversation, then they have a culture. Bird-David says 'culture is not the preserve of humans, but is evident (when seen as those indigenous peoples see things) among other-than-human persons too'. The animist perspective is that everything lives and is involved in culture, and that culture can include other persons human or non-human. In my journal Stephan Harding invites us to 'touch the trees and plants as if they can feel your touch.' Trees can give and receive touch, just as rocks can give gifts to humans and also receive gifts that initiate relationships. Let’s go back to the idea of eco-responsibility: by giving to the world, we will receive gifts back. 'Animism promises the enrichment of human cultures by fuller engagement with what is too often taken as background or resource available to the construction of culture'. If we can avoid the idea that nature is used to create human culture, and instead realise that nature=culture, then all of life can share in relationship. This is what I experienced with Andy's singing, dancing, and the Wassailing ceremony. We give gifts of our culture: music, dancing, bread and cider, that we may receive the gifts of the trees' culture: the fruit. This is far from using the trees as a 'resource available to construction of culture' (i.e. the apples for cider), but a tradition of equal reciprocity. Snyder’s phrase reflects this: ‘performance is currency in the deep world’s gift economy’. This idea of giving and receiving through performance (the Wassailing rituals), allows humans to understand what it means to lose something they would rather keep (the bread and cider). ‘What the creatures have to lose in the gift economy is their lives. What the people have to lose is their false sense of themselves as superior’. We are taught humility. Pat attempts to 'reach out to the ancient ones’ with this same humility, and this can be applied to any non-human person. 'Being silent so as to pay attention to elders may be matched by practising silence in the woods that are home to many of your other-than-human neighbours'. The exact advice that Nicola gives me about talking to trees: if we are still and silent in the woods we can hear the messages of the trees much clearer. Her method of introducing oneself to the tree first reflects Pat's humility with the rocks. This is also the underlying notion written on the piece of paper I was given, that glorious wish: 'May you grow to know a tree as an old friend.' In the conclusion of the journal I reflect that when people narrate their story, we cannot know what they actually experience. I will never really know what people mean when they say 'I speak to trees.' We can say the same about dream-telling. E. B. Tylor (1832-1917) says that attributing life, soul or spirit to inanimate objects comes from the 'primitive' inability to distinguish between dreams and waking consciousness. If a 'primitive' person dreams about a deceased relative, they assume that the persons' spirit has actually visited them. Out of dreams evolved the 'doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings in general'. Tylor's idea completely ignores: 1. Evidence of spirit visitation occurring in dreams. One Zulu man was visited so often in his sleep that he described his body as 'a house of dreams'; 2. That these dreams are experienced by adult, functioning human beings sharing the same time on earth as us, and that there is no primitiveness, childishness, or ignorance. This language 'simultaneously insists on the veracity of Western notions about personhood and materiality, while denigrating other understandings as childish and/or primitive’. Western belief at the time is that Europeans are the pinnacle of evolutionary development, and the word 'primitive' suggests that indigenous people are from a previous time. Tedlock addresses the misuse of 'typological time', saying that it denies that people are living at the same time, and is used as a 'distancing device'. 3. What people say they see in dreams is not necessarily what they actually experienced. I would like to elaborate on this last point. Tedlock discusses the idea that dreams are mental, private acts, never recorded during the actual occurrence, whereas dream accounts are public social performances shared after the dream. Some dream workers say that they can recover the dream itself through producing a dream-report, but Tedlock believes this cannot be the case. The same principles can be applied when a person describes communication with a tree: the conversation is a mental, emotional or soul-felt private act, rarely recorded during the actual occurrence, and the account of the conversation is shared in an appropriate context. The speaker chooses an audience (usually one open to the idea of speaking to trees), and an auditory or visual modality, with all its limitations. So we get the multi-performance list that I describe in the journal: 'Jenny watches, Andy sings, Steph knows, Nicola hears, Stephan touches, and Pat gives and receives'. Each person describes connections with nature in these ways, in an attempt to explain to the listener what they mean, but the listener can never know what the speaker truly experiences. The issue may be in the limitations of language (or music, or art). Tedlock calls this the 'basic axiom of semantics'- the word is not the object and 'dream narratives are not dreams': neither narrating nor re-enacting can recover dream experiences. Neither narrating nor re-enacting the event of speaking to a tree can recover the communicative experience. I discovered this through my drawing of the tree.

I came to the tree in respect and humility; I asked the tree permission to communicate with it: I gave what I had to give. And the tree communicated with me in a beautiful way. I saw visions of coloured light, purple and gold concentric rings at the top, and lines of different coloured light in a sphere around the bottom. Outside the tree was dark with little spots of light here and there. I realised the darkness is what the tree experiences: it has no eyes or ears to sense the world as we do. Instead the tree senses other beings as energy fields, like little spots of light, as they (birds, wind, grass, insects, me) enter the trees' own energetic sphere. I sensed the truth of the tree, I drew it, and I used words to describe it just now. But no one will ever know what I truly experienced.

4 Comments

|

Archives

April 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed