|

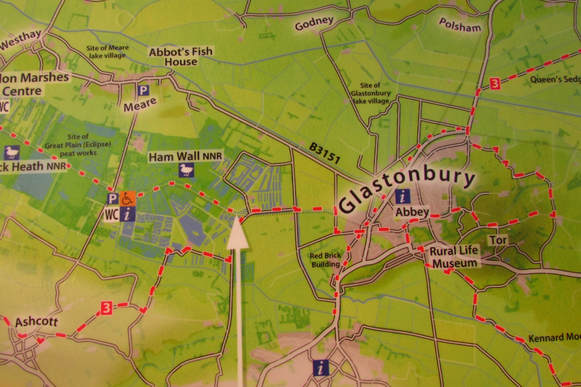

Northern lights teaching shoaling fish teaching swarming flies teaching clouding ink would never learn the – Ghostly swirling surging whirling melting murmuration of starling flock. - Robert MacFarlane The aim of this study is to discuss the meaning of sacred landscape by exploring the Somerset Levels phenomenologically, and to answer these questions: is the Somerset Levels a sacred landscape? Does the presence of Starling murmurations enhance that sacredness? Is sacredness a human construct? The most spiritual encounter I have had around Glastonbury is observing the Starling murmurations, which occur on the Somerset Levels at sunrise and sunset every day between November and February. Glastonbury and the surrounding landscape have many sacred features and stories: mythological, archaeological and historical. So what is it about this phenomenon of the Starling murmurations that has drawn me in and made me feel more connected to the landscape of my chosen home? Starlings at Ham Wall, Avalon Marshes, with a view of Glastonbury Tor. My study utilises literature on the natural history, archaeology, and legends of the area, and on creation mythology. Academic research includes literature on sacred landscape and phenomenology. My phenomenological research included visiting Ham Wall for the Starling murmurations, and creating a reflective journal about my own observations, and the reactions of others. My photographs illustrate these observations. Tilley defines phenomenology as 'the manner in which people experience and understand the world' (Tilley 1994: 12). Tilley advocates a multi-sensory approach: 'landscape is simultaneously a visionscape, a touchscape, a soundscape, a smellscape and a tastescape' (Tilley 2010: 27-28). During my research I watched the Starling murmurations, I heard them flying and chattering on the roost, I touched the water and reed-beds, I smelled the moors, but (to be honest), I didn't feel comfortable tasting anything. Tilley points out: tasting is the most intimate of the senses. The limitations of this study are that we see further than we hear, smell and touch. Birder Dan Brown understands this, however ‘some of the best birding experiences involve sound (lots of it), and even smell' (Brown 2017: 13). Tilley (2010) tells us how to research a landscape: firstly one must develop feelings for it, which I achieved by visiting Ham Wall around twenty times. Secondly is to visit places of prehistoric significance: I visited ancient Glastonbury Lake Village, Meare Lake Village, and Wirral Hill. Next is to re-visit in different seasons, times of day and weathers. I am limited to visiting at sunrise and sunset, in winter, but I did experience different weathers. I also ensured to approach from different directions, and to follow paths of movement and features in the landscape. Lastly is to draw together observations and experiences into an interpretation, which is what this study entails. The most important aspect of a phenomenological study is the feelings the place invokes. I chose to study the Starling murmurations because the experience has the most divine emotion attached to it. Brown describes how 'Birds are amazing, they illicit a complete spectrum of emotion in us... we express awe at their phenomenal migrations…' (Brown 2017: 8). For me, this ‘awe’ is the definition of sacred. Ham Wall History The Avalon Marshes is a wetland habitat covering 5 square miles of the northern Somerset Levels, created from worked-out peat diggings. The Ham Wall section is about 575 acres (230 ha) of land, managed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) since 1994. The RSPB describe the process of creating wetland from peat-works: 'After the peat has been extracted down to the level of the clay beneath and with the cessation of artificial drainage, the large holes that remain gradually fill with water to the levels held in surrounding ditches. The RSPB believed that this offered an ideal opportunity to help replace some of the wetland habitats that are continually under threat and being lost elsewhere in the country' (http://ncosbirds.org.uk/RSPB_Ham_Wall_introduction.pdf). Peat Works Can a human-constructed moor be considered sacred? Do the Starling murmurations enhance that sacredness? Bernard Storer (1985) tells us that as pasture-land increased during the 18th Century, the pasture-grazing Starlings appeared: they are not part of the ancient story of this landscape. Did human beings ever consider the Levels sacred? Historian Desmond Hawkins tells us of the paradox of the Levels that are 'at once more wild and primitive and yet more artificial than almost any other part of England' (Hawkins 1973: 17). During my explorations of the area I had to keep this in mind. I visited the site of the Meare Lake Village East, dated around 2000 years ago (Minnit and Coles 7: 2006): Why did the people choose to live in this particular spot? What did it look like then? So hard to imagine – Reflective Journal 30/11/17 The site of Meare Lake Village East, as seen from the highest mound, looking north. Tilley says through ‘naming... places become invested with meaning and significance' (Tilley 1994: 17). The name 'Ham Wall' has both wild and artificial meaning: Ham is ‘a low area of land that always floods', and Wall, ‘a bank or construction… to hold back water' (NCOS website). We can look at this etymology to consider how a landscape is at once humanised and natural. The Starling Murmurations Observing Starling flocks is like ‘watching an enormous lava lamp as these huge masses twist and stretch, condense and widen' (Brown 2017: 162). Slithering snakes, pulsing jellyfish, swimming whales- these are the visions I saw in the birds. One father exclaimed to his son ‘look, now it’s a dinosaur!’ – Reflective Journal 13/12/17 The word ‘murmuration’ comes from the sound: ‘a sudden change of direction by a super flock can sound like waves breaking on a pebble beach' (Brown 2017: 162). Storer describes Starling groups feeding by moving over the field, probing the ground. Those at the back leapfrog over those at the front to get food: 'the whole effect is of the Starling flock flowing smoothly and harmoniously across the field' (Storer 121: 1985). Shortly after reading this I saw it for myself: an incredible sight! When the Starlings settle down for the night: I listen to the chattering of thousands of birds now hidden in the reeds. B says it sounds like water trickling over rocks, or a waterfall. If air had sound as it flowed over rocks, this is it... I feel the sun-fire setting on the horizon, the air creatures settling down to roost in the water, and me, the earth-being, silently watching - Reflective Journal 13/11/17 Therefore the Starlings can be associated with the four elements: fire, air, water and earth (where they feed). Their migrations also reflect the seasons. Peak numbers arrive around winter solstice, when the Starlings at Ham Wall are in excess of 500,000 (RSPB Website). The incredible shapes of the murmurations over Ham Wall Literature Review To consider this question we must first define 'sacred landscape', and discuss whether places are intrinsically sacred, or whether people create them. Durkheim considers sacred space a human construct, and religion exists 'because human beings exist only as social beings and in a humanly shaped world' (Field 1995: xix). If nature cannot be separated from human belief, any place is 'sacred' if we believe it to be. The first of Lane’s (2016) four axioms is that a sacred place is often an ordinary place set apart and made extraordinary because of a story. Tilley rejects the idea of landscape as a mental construct: if a landscape is drawn into the day-to-day lives of people, it possess its own powers: 'The Spirit of Place may be held to reside in a landscape' (Tilley 1994: 26). Some places are 'ignored, condemned to inertia, while others are activated through use or presence' (Tilley 1994: 29). Is Ham Wall landscape 'activated through use or presence', because of the Starling murmurations? Today around 100 people watched the spectacle. When the Starlings arrived I could hear wows and gasps, 'look, here they come' and 'that was a great one': an audience enraptured – Reflective Journal 26.12.17 the audience at Ham Wall Is this landscape ‘activated’ by the people, or the Starlings, or both? Tim Ingold describes how 'a parliament of lines' (Ingold 2008: YouTube), joins together to create a knot. By observing the Starling murmurations, we 'join with the thing in its thing-ing' (Ingold 2008: YouTube). To inhabit a landscape is to join in the processes of formation. A sense of wonder is created by the feeling of ‘belonging’. Each Starling has its place, all are welcome; none are left out. I have my place too: down here, observing. I long to be a part of their movement, to belong with them, to be closer – Reflective Journal 16.12.17 Lane’s (2016) second axiom says one can move through a sacred place and not be present to it. If you are present, then you feel like you belong, as I describe above. What you long for is already within you, but you cannot realise this without wilderness. Martin Heidegger (1993) discusses the fourfold: sky, divinities, earth and mortals. Sacred spaces exist where the fourfold come together. The Starlings remind me of the fourfold: the sky is where the performance happens; divinity is in the awe and wonder we feel; earth is reflected in the creatures we share our planet with; our mortality (our own essence within the fourfold) is reflected in feelings of ‘longing’. Ham Wall has a dedicated space to reflect on our mortality: an otter statue where people place plaques to remember loved ones. ‘A Quiet Place for Reflection…where you can remember your loved ones’- RSPB sign Is it the presence of people that contributes to the ‘sacredness’ of a place? Tilley mentions the 'Spirit of Place' (Tilley 1994: 26), which J.D. Hughes defines as 'the power that is manifested in sacred space' (Hughes 1991: 15). Lane’s (2016) third axiom is that a sacred place is not chosen, it chooses: it draws people to it. Therefore the sacredness must come before the people. Those who enter may experience 'healing, meaning, transformation, strength or connectedness with nature' (Hughes 1991: 15). Hughes comments that those who create nature protection reservations, like Ham Wall, have a sense of this spirit: 'the place where natural ecosystems are intact and functioning in the full spectrum of their beauty is the place where spirit is most manifest' (Hughes 1991: 25). Could this be true of the Somerset Levels? Though man-made, the landscape is wild and functioning in its full spectrum of beauty. Findings/ Discussion The Gaia Foundations’ operational definition of a sacred site is: ‘a place in the landscape, occasionally over or under water, which is especially revered by a people, culture, or likely religious observance’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12). Using this definition I can discuss whether or not the Ham Wall is a sacred site. Ham Wall is a landscape with water, but is it especially revered? Initial observation would say not: there is no temple, religious focus, or particular culture that reveres it. In fact the opposite: for most of its history the Levels are a ‘wasteland’ (Storer 13: 1985). However: 'peace, quiet, a sense of space and of 'oldness' are the feelings which it engenders' (Storer 13: 1985). This ‘oldness’ is reflected in the stories of the Somerset Levels. Lane says: 'above all else, sacred place is ''storied place''' (Lane 2001: 15). Historian Ray Gibbs says: 'That earlier landscape (or waterscape, if you prefer!) obviously was the real world of the Glastonbury legends, the place where it all began' (Gibbs 15: 1988). Legends of King Arthur are connected to the water: the great waters and conical Tor must have been seen as spectacular and 'other-worldly' (Gibbs 20: 1988). The legend of Joseph of Arimethea, Jesus’ great-uncle, describes his journey to Glastonbury with eleven companions, stopping at Weary-all (Wirral) Hill, where his staff became a Holy Thorn tree. Joseph was subsequently given the XII Hides of Glastonbury, much of which lay on the Somerset Levels. The XII Hides revealed 'a distinct other-worldly feeling about the islands' (Gibbs 79: 1988). Wirral Hill’s Holy Thorn Tree looking out onto the water-logged Somerset Levels. These legends suggest the watery area was revered in the past, but how can we know what previous people really thought? Eliade was criticised for considering that human beings, no matter where or when they exist, all 'share a common level of experience' (Studshill 185: 2000). Can we say that because I experience the Somerset Levels as sacred, so did previous peoples? People today have experiences suggesting the Somerset Levels are still revered on some level, and connection to nature is its medium. Hillary Angelo considers our apparent ‘disconnection’ from nature is only that ‘the empirical nature of our connections is changing' (Angelo 361: 2013). It is not a 'modern absence of experience, but a quality of experience formed... through different patterns of institutional context, phenomenal experience, and structures of feeling' (Angelo 361: 2013). Who is to say that I am less ‘connected’ than my ancestors? Everyone I speak to know the Starlings in some capacity. My friend danced with them at sunrise in her garden, and my colleague commented 'don't stand under the little buggers!' These experiences have something in common: a touch with the wild, reminding us that we are not separate, even if sometimes we would wish to be! - Reflective Journal 10/12/17 Eliade (in Studshill 2000) tells us that humanity was once more connected, open and viewed the world as more sacred than we do, but he offers no historical accounts of when this connection ceased and the West fell from grace. Simon Schama comments: 'only the Paleolithic cave-dwellers... are exempted from this original sin of civilization' (Schama 13: 1995). Schama sees the paradox of a landscape being at once wild and artificial as nothing new: 'Even the landscape that we suppose to be most free of our culture may turn out, on closer inspection, to be its product’ (Schama 9: 1995), and this should be celebrated. Heidegger believes the fundamental character of humanity dwelling on the earth is 'to spare... to not do harm but to protect' (Heidegger 1993: 351), meaning to 'set something free into its own essence' (Heidegger 1993: 352). This does not mean free from human interference. We could say that man-made Ham Wall, which in its perfection invited the Starlings, set the landscape 'free into its own essence' (Heidegger 1993: 352). I have felt the truth of this. The most sacred moments I have experienced around Glastonbury have not involved the ancient legends, the well-known sacred sites, or any place written about in the history books, but human-constructed moor and a species that arrived in the 18th century. However, the ancient myths and legends probably contributed to the formation of the Levels today. Ingold sees every thread of history, archaeology, myth and legend as entangled into a 'tapestry of life nature is weaving' (Ingold 2008: YouTube). Perhaps the land itself has always been sacred, and the memories are still there. Schama (1995) says that many assume Western culture evolved by letting go of our nature myths, but he disagrees: they are still with us. Can we still find them in the Somerset Levels? Genesis says: 'In the beginning God created the heavens and Earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was on the face of the deep; and the spirit of God was moving over the face of the water' (Genesis in Casey 12: 1997). Other traditions describe the primal-mists, or 'chaos fluid' (Casey 17: 1997) as in the Egyptian Book of the Dead. The Hindu tradition says that 'Brahma creates in the morning and at night the three worlds... Earth, Heaven and Hell are reduced to chaos' (Henderson and Oakes 55: 1996). At the end: 'every single atom dissolves into the primal, pure waters of eternity, whence all originally arose. Everything then goes back to the fathomless, wild infinity of the ocean' (Henderson and Oakes 57: 1996). In these creation myths, and many others, a Being always appears and creates something of this chaos, or nothing-ness (even though there is something- the water). The idea of watery-chaos produces panic: we have to master it! 'To master is not to bring into being in the first place but to control and shape that which has already been brought into existence' (Casey 23-24: 1997). Out of the pre-existing waters comes creation. Considering the history of the Somerset Levels, this idea of creation being born out of watery-chaos is rampant. 'The main issue down the centuries has been to establish and assure the conditions in which human beings could live' (Hawkins 17: 1973): to master it. This watery-chaos has not been easily tamed: 'Time and again in its history there has been a swift irruption of flood-water, inundating villages and destroying life and property' (Hawkins 17: 1973). It took the best part of 1000 years to create what we have now. The similarity between creation myths and the history of the Levels is: before was watery-chaos, then creation, then order, light and beauty. If I knew nothing of its history, I would consider the Levels now ordered, light and beautiful. That the landscape itself still holds nature myths feels very real to me. No matter what man does, nature is always perfect. The Levels have probably been 'order, light and beauty' to people in the past, those who succeeded in 'mastering' their landscape. Part of mastering is acceptance of what cannot be mastered. The dimness, rain and cloudy sky only added to the surreal energy of the place, and you could imagine it as chaos. How did ancient people living on the land feel on foreboding nights like this? - Reflective Journal 23/11/17 a dark and gloomy night at Ham Wall The Gaia Foundation lists nineteen points to define a sacred site: even if only one corresponds, the place can be considered sacred. The following points apply to the Somerset Levels. A sacred site is: ‘a natural topographical feature;… recognised as carrying special manifestations of wildlife, natural phenomena, ecological balance;… a memorial or mnemonic to a key recent or past event in history, legend, or myth’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12). The first two points are clearly the case with Ham Wall, and with the third I consider that creation myths, the Arthurian and Arimathean legends could hold these mnemonic messages in the memory of this landscape. The Spiritual definitions consider that a sacred site has ‘palpable and special energy or power which is clearly discernible from the landscape’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12): the Starling murmurations create a palpable and special energy at Ham Wall, clearly discernible from similar sites, and ‘is a place of spiritual transformation for individual persons or the community’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12): my own experience is an example, as viewing the Starling murmurations instilled in me a sense of wonder that helped me fall in love with my chosen home. This leads to another definition we could consider adding to these points: sacred places invoke a sense of 'awe, emotion, wonder or anguish' (Tilley 1994: 16). Today was full of wows! ‘'It's epic'' one guy said to me - Reflective Journal Epic murmurations with an epic view! Hughes says 'the unmistakable Indian attitude toward nature is appreciation varying from calm enjoyment to awestruck wonder' (Hughes 1996: 135). To these people, 'sunrise was the greatest daily event' (Hughes 1996: 143). This morning the marshes were full of joyful birds of varying species, making a myriad of sounds, chasing around, standing silently alone or hopping around under our feet. I could feel from them a palpable ecstasy of being alive: thank God the sun has risen! – Reflective Journal 27/12/17 Sacredness comes in the seasonal and daily repetitions of the Starling murmurations at Ham Wall. Writer Rachel Carson sums this up nicely: ‘There is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migrations of the birds, the ebb and flow of the tides... There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature - the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter' (Carson 1996: 24). Conclusion In conclusion I would like to address the Gaia Foundation definition of sacred sites and those of the nineteen points which indicate that the Somerset Levels (with Ham Wall being the main location) is a sacred landscape, and the Starling murmurations enhance that sacredness, using my reflective journal and academic literature to support my arguments. Ham Wall is definitely ‘a place in the landscape, occasionally over or under water’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12). It could also be a place ‘especially revered by a people, culture, or likely religious observance’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12), if we agree with Durkheim (in Field 1995: xix) that something is sacred if people believe it to be. People ‘revere’ this landscape because they believe it to be a special place, due to feeling connection to and wonder at the Starling murmurations. Ham Wall is ‘a natural topographical feature’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12), even though it is man-made. It is a place ‘functioning in the full spectrum of [its] beauty' (Hughes 1991: 25), and its artificial creation means it has been set 'free into its own essence' (Heidegger 1993: 352). The Starling murmurations enhance this essence. Ham Wall is ‘recognised as carrying special manifestations of wildlife, natural phenomena, ecological balance’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12), which is shown to its fullest in the Starling murmurations. We see seasonal and daily balance during winter sunrise and sunset, which brings us ‘something infinitely healing’ (Carson 1996: 24). The Somerset Levels (though not necessarily Ham Wall specifically), shows evidence of ‘a memorial or mnemonic to a key recent or past event in history, legend, or myth’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12). History, archaeology, legend and landscape memory lie in the water itself: in its ethereal quality, in the chaos of the floods, and the in mastery of the landscape, all of which is reflected in creation mythology. This mythology manifests in the Arthurian and Arimathean legends, and in the history of a landscape that took many generations to create out of chaos ‘conditions in which human beings could live' (Hawkins 17: 1973). Ham Wall has ‘palpable and special energy or power which is clearly discernible from the landscape’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12), enhanced by the Starling murmurations. It has a 'Spirit of Place' (Tilley 1994: 26), which is the ‘palpable ecstasy of being alive’ I felt from all the species of bird one dawn. However, as sacred places invoke a sense of 'awe, emotion, wonder or anguish' (Tilley 1994: 16), watching the Starlings does enhance the Spirit of Place. Finally, Ham Wall ‘is a place of spiritual transformation for individual persons or the community’ (Thorley and Gunn 2008: 12), as those who enter it may experience 'healing, meaning, transformation, strength or connectedness with nature' (Hughes 1991: 15). This is reflected in my feelings of wonder, of belonging, connectedness to nature, and love for my home, all of which were enhanced by the Starling murmurations. Although Lane (2016) says that to be in a sacred landscape you must be present to it, suggesting that not everyone would consider the Somerset Levels as sacred, I do not think this diminishes its sacredness. He also says: what you long for is already within you, but it is wilderness (and the Starlings) that helps you realise it. Related

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed