|

This is an essay I wrote for the MA module at Schumacher College, Indigeny Today.

If you would like any references please let me know, I'm happy to send you them. I have taken excerpts from my journal throughout March 2018, during the Indigeny Today module, which refer to the theme of ‘Time’, including speed, Right Time, ancestors, and future generations. I highlight the excerpts in italics throughout this paper. I consider each excerpt’s relevance to how indigenous worldviews can inform western worldviews about time. I aim to illuminate how incorporating different notions of time can help humanity create ideals which orientate towards thriving life. Frederique Apffel-Marglin (2011) believes that time is not just a passage, regardless of humans, but: ‘the achievement of the continuation of a liveable world made collectively, non-anthropocentrically’ (Apffel-Marglin 2011: 163). Indigenous peoples have achieved this for thousands of years, so considering their views is paramount. On Time Colin Campbell says if we record a story, poem or song using technology, we freeze it in time, so it is no longer ‘’alive’’. Indigenous peoples often view time as cyclical: ‘According to Indigenous science, everything that exists is bound within the great cycle of time’ (Peat 1994: 179). Daily practices are bound up within this worldview: ‘You have noticed that everything the Indian does is in a circle, and that is because the Power of the World always works in circles…’ (Black Elk in Murphy 2013: 44-45). David Abram (1996) believes linear time was created along with the Hebrew alphabet: ‘A new sense of time as a non-repeating sequence begins to make itself felt over and against the ceaseless cycling of the cosmos’ (Abram 1996: 195). Recording history through writing created static time, just as Colin expresses above how stories, poems and songs are frozen in time when they are recorded: they are no longer ‘alive’. On Speed I feel frustrated because I wish Colin was here longer. I could listen to him for hours. How can we possibly learn all he has to teach us in only one week? I think he feels it too, the constraints of time and schedule, very different from the cultures of which he speaks. Here, I express frustration with the short time we have to learn from Colin. Within indigenous societies, it takes years of patient listening to learn wisdom from ones elders, as Winona Wheeler (2005) comments: ‘Within the community, I always hear elders say, if you want to learn, be quiet and pay attention. Only through being part of the community over a period of time and developing trust does knowledge come to you-very slowly’ (Wheeler in Smith 2005: 109). For academics and those within western education, who are used to acquiring knowledge quickly, this can be frustrating. I feel that tension between the worldviews, and so (I think) does Colin. David W. Orr (1996) reflects on slow knowledge, saying that ‘the only knowledge we've ever been able to count on for consistently good effect over the long run is knowledge that has been acquired slowly through cultural maturation’ (Orr 1996: 700). This knowledge fits into a particular ecological and cultural context. Also, ‘Slow knowledge really isn't slow at all… true knowledge takes time, and it always will’ (Orr 1996: 702). He stresses the social aspect of this: ‘slow knowledge occurs incrementally through the process of community learning’ (Orr 1996: 700); through affection for the community. Therefore the aspect of time involving the speed of acquiring knowledge is a social one, particularly involving respect for ones elders. Busy minds and lifestyles create what Colin calls ‘random heat’. Slow down and it’s safer and less unpredictable. Mongolians call this the ‘wind horse’, meaning a perturbed psyche. We must cultivate coolness by slowing down. Older people carry this coolness, but they are seen as unproductive and worthless in our society, because they are slow. We went to the River Dart to perform a ceremony. Pat McGabe says that when we do this, we can consciously slow to the rhythm of the other-than-human beings around us: the river, the trees, the birds. Colin’s notion of ’random heat’ could be equated with increasing speed. The drive behind western increase of speed is productiveness: older people are slower, and are therefore less productive, and less valuable. Whereas Colin implies that in indigenous cultures older people are more valuable, because of their ‘coolness’. Likewise, Colin’s ’coolness’ can be equated with ‘slowness’. Pat agrees that slower is better, because if when a ceremony is performed, the participant slows to the frequency of the surrounding other-than-human beings, they can connect deeper. Paul Cilliers (2007) believes that actually ‘the cult of speed… related to efficiency, is a destructive one’ (Cilliers 2007: 1), and a slower approach is necessary for survival and ‘allows us to cope with a complex world better’ (Cilliers 2007: 1). Joanna Macy (2007) agrees: ‘speed and haste… are inherently violent’ (Macy 2007: 178), and the natural systems that sustain us move slower than we do. Western thought has occasionally confused slowness with ‘stupid-ness’. ‘How other people organized their daily lives fascinated and horrified Western observers…’ (Smith 2012: 56), who saw (and some still see) native people as lazy and indolent, with low attention spans. Kathleen Pickering (2004) alludes to this in her discussion of Lakota people today. Despite the US governments’ best efforts, the people have still not fully adapted to ‘clock-time’, because for them, ‘Economic opportunity is defined by maintaining good social relationships, not by performing according to an abstracted clock’ (Pickering 2004: 92). Lakota people saw wage-work as lazy because ‘it limited work to only eight hours a day regardless of whether the work was done’ (Pickering 2004: 93). Wage-workers and academics may ‘find ourselves moving too fast for the cultivation of friendships and cross-cultural solidarity, which have their own tempo’ (Macy 2007: 177). On Right Time Rituals in Africa have no calendrical or clock time. They begin at the ‘right time’. David Luke said something similar about the Huichol people of Mexico. He asked when they would leave for their pilgrimage and was told ‘soon’: he waited another three days before they left! Sometimes they were packed up and on the move before they’d finished eating, because the time was right to go! Here, David alludes to another phenomenon that baffles western observers: that of ‘right time’. Peat (1994) says that ‘Indian time’ confuses non-native visitors to Native Indian communities, as they may turn up at a powwow ‘in good time only to find what appears to be a total absence of any organization-the grand entry is not taking place until later in the afternoon’ (Peat 1994: 201), just as David waited three days for a pilgrimage to begin. Each of the newly-rejuvenated Native American Winter Dances: ‘is somewhat different and comes about through a spirit call to the shaman-sponsor rather than a human-determined calendar or clock time’ (Grim and Tucker 2014: 131). When preparing for the steam ritual, we were on occasion impatient to get going, but waiting for the stones to bake was part of the experience. We asked Colin when we’d begin and what the plan was. He couldn’t tell us, and so we relaxed into the task, and a sense of community unfolded. We felt this sense of frustration with not knowing exactly when the steam ritual will begin. However, Native people have no sense of urgency, and ‘tend to meet and act only ‘’when the time is right’’’ (Peat 1994: 202). ’A ceremony begins… It is at that moment that a time is created for the ceremony’ (Peat 1994: 204), which makes sense in terms of cyclic time: ‘In the paradox of cyclic time this moment did not exist until the ceremony began, but once it had been created it made its influence felt within the cycles of time that stretch back to the days, weeks, and years that precede the ceremony’ (Peat 1994: 204). Once we relaxed into not-knowing the time the steam ritual would begin, a sense of community unfolded among our group. This sociable context is paramount to many indigenous communities. Yasmine Musharbash (2007) discusses boredom in Australian Aborigine settlements. The ‘boringness of a place is created by the absence of people… and a lack of social interaction and engagement’ (Musharbash 2007: 310). ‘No Warlpiri person would ever call ritual boring’ (Musharbash 2007: 311), because it is set in a sociable context. The notion of ‘right time’ creates this social cohesion, as ‘when the group as a whole feels that the right moment of time has arrived, they will act in a consensual way’ (Peat 1994: 202). On Ancestors I picked the ‘Elephant’ card, and Colin said it was about remembering ancestors. Elephants remember ancestral trauma from previous generations, bury their dead and mourn them. A great way to live is to remember death at every moment. All indigenous traditions know about the elephant. The excerpt above describes how elephants remember ancestral traumas and bury their dead. Cilliers (2007) writes about the importance of slowness in remembering. Memory carries something over from the past to the future, and so the past is active in the present. A persons’ memory must distinguish between information and noise, so cannot follow everything in its environment. There must be time for reflection and interpretation. ‘The argument for slowness is actually an argument for appropriate speed’ (Cilliers 2007: 6). Perhaps elephants use the perfect speed to reflect and interpret, in order to remember generations past. If ‘a great way to live is to remember death’, and if ‘All Indigenous traditions know about the elephant’, then perhaps indigenous peoples remember their dead in the same way. Munn (1992) describes how Apache ancestral place-names orient listeners' minds to ‘look 'forward' into space’, thus positioning them to ‘look 'backward' into time’. Place-names help people ‘imagine [themselves] ... standing in their 'ancestors’ tracks’ (Munn 1992: 113). Incorporated into the viewers’ biography, ancestral events become a form of ‘lived history’ (Munn 1992: 113). With Pat we invoke our ancestral lineage going all the way back. I can see my ancestors lining up behind me, stretching into the past. In front of me are the generations to come. I see many future generations, and feel whole. Colin says that ‘in the old days’, this was seen as the veins that connect us and the universe. The Nayaka ‘do not assume an irreversible split’ between the past and present ‘as if the two can never meet’ (Bird-David 2004: 407). Their ancestors are sensed ‘as relatives who arrive before them, ones whom they join rather than replace, and with whom they share a home’ (Bird-David 2004: 407). The sharing of a home suggests sociability with all these relatives, ‘most importantly through dancing, singing, and, above all, talking with their invoked manifestations’ (Bird-David 2004: 407). Therefore ancestors are a very real section of indigenous societies, not isolated in the past, but tangibly in the present. This is perhaps similar to my description above of the ancestral meditation with Pat, imagining my ancestors stretching out behind me. I also see them in front of me, as future generations, which I will discuss below. Colin describes this as ‘the veins that connect us and the universe’. Colin's allusion to ‘the old days’ refers to the time before the African communities he speaks of disbanded. In a sense their history began with the appearance of imperialism and colonialism, at ‘the point at which society moves from prehistoric to historic… Traditional indigenous knowledge ceased, in this view, when it came into contact with ‘modern societies’ (Smith 2012: 58). There is now a sense of distance between us and Colin’s traditional knowledge. This knowledge, however, does not come through written history, but oral traditions, and therefore as Colin speaks, his tradition is still alive. Ancestral knowledge allows a much longer time frame of record keeping, meaning the cultures survive for many generations. Peat (1994) speaks of traditional stories that ‘reach back hundreds, thousands, and maybe tens of thousands of years. They enable a Native person to enter into a relationship with the great cycles of time, the history of the people, the land, and the cosmos’ (Peat 1994: 78). This is what I refer to in the above excerpt as the ‘longer time frame of record keeping’. Abram calls it ‘Mythic Time’: ‘one actually becomes the ancestral being, and thus rejuvenates the emergent order of the world’ (Abram 1996: 187). In Yokut culture the world dies at the end of each year, and it is humanity’s duty to assure it is annually reborn. Therefore ‘the behaviour of successive generations of men and other living things is critical to the maintenance of cosmic continuity and hence to prevent a reversion to the original chaos’ (Goldsmith 1996: 125). This long tradition of record keeping aided indigenous cultures to survive for so many generations. On Future Generations Pat says we are experiencing the consequences of decisions made seven generations ago without putting thriving life at the centre. We need to think now about how seven generations ahead will be affected by decisions we make now. Jiordi expresses speechlessness about how these future generations keep showing up. As Pat suggests here, the western worldview could be seen as ‘exclusively concerned with immediate political or economic benefits and its promoters show absolutely no interest in the consequences of such behaviour for future generations; for the latter are not players in today’s political and economic games: they neither vote, nor save, nor invest, nor produce, nor consume. Why then should they be consulted?’ (Goldsmith 1996: 134). Macy (2007) believes this is a relatively new phenomenon. Our historical monuments and art are proof that humanity naturally thinks in terms of enduring beyond one lifetime. This capacity was lost with the creation of the atomic bomb, because it ‘ruptured our sense of biological continuity and our felt connections with past or future’ (Macy 2007: 171). For the first time people could imagine how humanity itself could end the world. Timothy Morton (2010) advocates for the ecological thought, because it ‘thinks forward. It knows we have only just begun, like someone waking up from a dream’ (Morton 2010: 98). Macy (2007) sees the New Age obsession with being ‘in the present’ as destructive, because it discourages this ‘thinking forward’. It is better to find a way of being in time, not to escape from it altogether. To do this, a good story could be adopted, reminiscent of indigenous cosmology. In remembering our evolution and ancestors, we make the future more real. As mentioned in the excerpt above, indigenous peoples often make decisions with consideration of seven generations ahead. The Guardianship Project ‘expresses what indigenous wisdom has embodied for centuries: to make decisions with regard for ‘’seven generations to come’’’ (Macy 2007: 198). This helps people to imagine the world they wish to create and take steps toward achieving it. Jiordi’s expression of surprise at how these young people keep showing up in the world is reflected in Macy’s comment: ‘the beings of the future and their claim on life have come to seem so real to me that I sense them hovering, like a cloud of witnesses’. I consider that a society with a healthy regard to time feels that future generations are already part of their social network. Conclusion I conclude that indigenous worldviews regarding time are commonly grounded in keeping the community connected with each other, other-than-human beings, ancestors and future generations. These worldviews could help western people create ideals which orientate towards thriving life. Time is indeed ‘the achievement of the continuation of a liveable world made collectively, non-anthropocentrically’ (Apffel-Marglin 2011: 163). Elders must be listened to, and traditional, ancestral knowledge must be respected. ‘True knowledge takes time’ (Orr 1996: 702) and it is acquired in community. Through ceremony, people can slow down to the frequency of nature, and therefore connection with the other-than-human community is increased. This ‘slowness’, far from being lazy, actually increases the level of social interaction, collaborative work, and gives time for forming friendships. Rituals are sociable events that allow for social cohesion as the group decides together that the ‘time is right’ to begin. Ancestral memory and remembering the dead encourage a ‘lived history’ (Munn 1992: 113) of social relations with ancestors, who are the ‘veins that connect us and the universe’. Through oral traditions rather than written history, this ancestral memory reaches back thousands of years. This ‘longer time frame of record keeping’ allows for increased cultural survival, and ensures regeneration for future generations. Through finding a new cosmology and remembering the ancestors, a future reality is created. Future generations can then be included in societies’ current social networks, which could lead to slowing down, or even halting completely, the destruction of the world.

0 Comments

During the First World War women around the world were an indispensable part of the war effort. Their roles at home, in civic life, industry, nursing, and even those in military uniforms, were extremely important to the outcome of the war. What is the situation like now? Are women valued in the part they play in modern warfare? Are they enjoying the same rights as men when serving in combat? Women Fighters in History

Throughout human history, soldiers and military personnel have been mostly male figures. Occasionally an exceptional woman comes up in military leadership roles, such as Queen Boudicca, who led a revolution against the Romans in Britain, or Joan of Arc, who led the French against the British. In some wars, for example the American Civil War, women disguised themselves as men in order to fight for their country. In recent history, we only see women in combat when they are needed, as there is a lack of men to fight. During the First World War, Russia used an all-female unit, the only country to allow women to fight in direct combat. In World War II, hundreds of thousands of women served in British and German armies. The Soviet Union had many women on the front lines serving as medical staff and political officers, and they had all-female sniper units and pilots. Women served in resistance movements in Communist Russia and Yugoslavia. After 1945, combat roles for women were halted and their services all but forgotten. After WWII, women served in the army in only 3 countries. The Democratic Republic of the Congo trained 150 women as para-commandos in 1967. During the Eritrean-Ethiopian War in 1999, a quarter of Eritrean soldiers were women. Israel became the first country to have mandatory conscription for women in 1948. Women in the Military Now In 1989, Canada ordered the full integration of women in the Canadian Armed Forces. Israel didn’t make this leap until 2000, and Australia still hasn’t, but plans to open up combat jobs to women in 2017. The first country to allow women to serve on submarines was Norway in 1985, and this year they included women in their compulsory military service. Sweden has similarly opened up to female roles, but so far only 5.5% of officers are women. New Zealand has no restrictions at all on roles for women, and so far women have made it into all sectors except the Special Air Service. Sri Lanka is open to female roles, but there are many limitations in ‘direct combat’ duties. Turkish women have voluntarily taken part in defending their country throughout Turkey’s history, including during WWI. Turkish independence was won with the heroism of Turkish women. Today, women are employed in the Turkish Armed Forces, because of ‘’needing qualified women officers in suitable branches and ranks’’. They serve all sectors except armour, infantry and submarines. In WWI and WWII women served in the United States army as Army Nurse Corps and Women’s Army Corps. They could enlist but could not have direct combat roles. In 1994 the military officially banned women from serving in combat, but in 2013 the ban was lifted. In the UK, women serve in the army but are still banned from frontline infantry roles, although this ban may be lifted soon. Some other European states also allow women to enter their armed forces. Objections Against Women in the Military

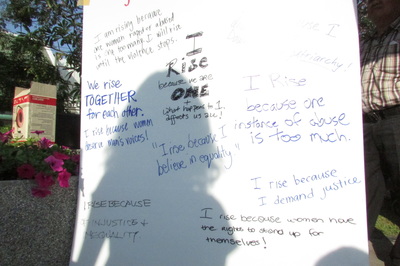

I remember being at university and watching a production of 'The Vagina Monologues'. I didn’t get it, felt extremely uncomfortable watching it, and didn’t really find it funny. Now when I think about it I know at age 19 I simply wasn’t ready to think about all the issues it brings up. Strange how almost 10 years later I would absolutely love to go and see it again, I know I would now understand perfectly and laugh and cry in all the right places. The Vagina Monologues was created by the wonderful Eve Ensler, a woman from New York who was abused by her father at a very young age. She wrote the novel ‘Insecure at Last: Losing It In Our Security Obsessed World’- on my reading list! – in which she describes the abuse. The book is about how people live today and the effort they make to keep themselves safe. Ensler wrote the play ‘The Good Body’ that explores how women from different cultures and backgrounds feel about their bodies in different situations. ‘I Am An Emotional Creature: the Secret Life of Girls of Around the World’ includes some very powerful stories and poems; monologues from real girls and women. The story describing how one woman escaped with her child from her rapist soldier captor in the Democratic Republic of Congo will always stay with me. Performances of 'The Vagina Monologues' play around the world inspired Eve Ensler to create V-Day, an organisation that promotes action against violence against women and girls. ‘One Billion Rising’ is the global protest event put on every year to give awareness about the one billion women and girls in the world that have been raped or beaten in their lifetime. The ‘V’ stands for Victory, Vagina, and Valentine- V-Day is the 14th February every year. One billion people dance on this day to promote justice and equality for women. www.onebillionrising.org/ Eve Ensler is one of the most inspirational women’s rights activists in the world today. Her stories about helping potential victims of Female Genital Mutilation in Kenya, victims of rape during war in the Congo, repressed women in Afghanistan, and lots else besides, are truly motivating to me. A woman who has suffered herself, and has risen up to give her energy to help so many others. Pictures from One Billion Rising, Chiang Mai, Thailand 14th February 2015 Eve Ensler shares her wisdom... Cocoa Production

Cocoa is grown in tropical regions around the Equator. The main cocoa producing countries are: Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon, Indonesia, Brazil and Ecuador. Most is grown on small family farms: only 5% is from large plantations. Growing cocoa is the livelihood for 40 to 50 million farmers worldwide. Their work is intensive, as the trees need constant care and attention, and they produce beans all year round. It takes a whole year’s crop to produce only half a kilo. Cocoa beans are grown in pods. When they are ripe the farmers hack them off with machetes. The pods are then manually split open and up to 50 beans are removed from each. The beans are fermented by heating in trays covered with banana leaves, or just left in the sun. This takes 5 to 8 days. Then they must be dried, which takes about a week. Once dried, the beans can be shipped off to the manufacturers. To the Global North The farmers sell the sacks of beans to intermediaries, who export them to the Global North. First they reach the grinding companies, who remove the shells, roast the beans, and ground them into cocoa liquor. This liquor is used to produce chocolate, cocoa powder or cocoa butter. Chocolate manufacturing is a huge business, and confectionary companies make high profits. Companies cut costs to compete with other companies by paying the cocoa farmers less. Most farmers now live on around 1.25 US dollars a day: about 6% of what the consumer pays for chocolate. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed