|

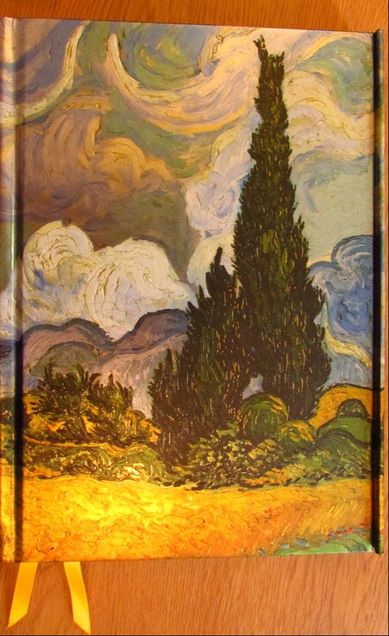

My final assignment for the Heavenly Discourses module of my MA in Ecology and Spirituality, is finished and submitted... I thought you might like to take a look... Sky Journal – On Clouds Rows and floes of angel hair And ice cream castles in the air And feather canyons everywhere I've looked at clouds that way But now they only block the sun They rain and snow on everyone So many things I would have done But clouds got in my way I've looked at clouds from both sides now From up and down and still somehow It's cloud's illusions I recall I really don't know clouds at all - Joni Mitchell (1968) Introduction The aim of this project is to explore the affect that clouds, and weather, have on the subject: myself. During the months of June to August 2018, I conducted research on the clouds, using my Sky Journal (Figure 2) to interview myself connecting with them. The journal entries were all made in Somerset, at different places, times of day, and weathers. Jane Goodall describes a moment, while immersed in the jungle; when a rapid weather change led her to profoundly feel ‘that self was utterly absent’ (Goodall in Taylor 2010: 29). She describes merging with the air and nature around her. I shall research how the sky, and in particular clouds, create in me a sense of oneness with my surroundings; how different clouds and weathers play with my emotions; and how different cultures’ stories and mythologies mirror cloud-experiences, through reflecting on images I see in clouds, and conversations held between myself and clouds. Methodology While conducting my research, I spent as much time as possible, at different times of day and in different weathers, observing clouds and reflecting on how they make me feel. I wrote notes in my Sky Journal about the time, place and weather conditions at the time, and any thoughts and feelings that arose for me during the observations. The journal is based on three places in Somerset: Glastonbury, Wells and the Somerset Levels. The research took place through the months of June to August 2018. I also include photographs of cloud-formations to support my research. I consider the views of phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961). His methodology is to watch the sky and feel himself plunging into it: ‘I abandon myself to it and plunge into this mystery... I am the sky itself as it is drawn together and unified... my consciousness is saturated with this limitless blue' (Merleau-Ponty in Ingold 2007: 29). I contemplate during this research whether I am ‘plunged into’ the sky, as Merleau-Ponty describes. Christopher Tilley’s (2004) exploration of landscape phenomenology suggests that while a painter observes a tree as he is painting it, so the tree observes the painter: not using eyes, but through effecting the painter (2004: 18). I reflect on how clouds affect my emotions through my observation of them: in affect my ‘painting’ is my reflective Sky Journal. David Abram defines phenomenology as the philosophy that gives ‘voice to the world from our experienced situation within it’ (Abram 2016: 47).Through this research I speak from within my experience of clouds. Literature Review My first research section is about sensing oneness with clouds and weather. Tim Ingold (2010) considers that by overwhelming the senses, wind and rain can ‘drown out the perception of contact with the ground’ (Ingold 2010: 131), to allow oneness with the sky itself. Alexandra Harris (2016) says that poet John Keats (1725-1821), while surrounded by cloud, disrupts boundaries between himself and clouds by asking: ‘what is a ‘thought’… but more of this mist? Turning himself inside-out, Keats makes the cloud around him a projection of his own mind’ (Harris 2016: 246). I also draw on the work of Peter Knight (2016), who describes how he received inspirational messages from the Dartmoor landscape, while immersed in cloud. Secondly I contemplate how weather plays with one’s emotions. Ingold considers that terrestrial inhabitants of Earth are constantly subject to weather, so that ‘The experience of weather lies at the root of our moods and motivations’ (Ingold 2010: 122). Stanley David Gedzelman’s (1990) work on Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) shows how his painting A Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City), reflects movement and emotion through the images of wave-clouds. I also draw on Nick Hunt’s (2018) work Winds of Awe and Fear on how extreme weather affects people emotionally. Thirdly I discuss how story and mythology mirror weather and clouds, through sky imagery and divinity. The word inspire is related to spirit, and to breathing: the air. So story and mythology can be said to have been inspired by the air, weather, and clouds. As Harris (2016: 12) points out, an ancient Christian image portrays Adam’s thoughts fashioned from clouds. I also draw on David Abram’s (1996) discussion of Native American cosmologies of air and wind, and his views on perception and communication between human and air. Oneness with the clouds Taylor (2010) describes Goodall’s experience of merging with nature: ‘she was deep in the forest with the chimpanzees when the weather changed rapidly, leading to one of her most profound experiences, which she considered truly mystical: ‘’Lost in awe at the beauty around me, I must have slipped into a state of heightened awareness… that self was utterly absent: I and the chimpanzees, the earth and trees and air, seemed to merge, to become one with the spirit power of life itself…’’’ (Taylor 2010: 29). Is it possible, while cloud-watching, for the self to become ‘utterly absent’? Phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty describes how, when sky-watching, ‘I abandon myself to it and plunge into this mystery... I am the sky itself as it is drawn together and unified... my consciousness is saturated with this limitless blue' (Merleau-Ponty in Ingold 2007: 29). Phenomenology is the philosophy that gives ‘voice to the world from our experienced situation within it’ (Abram 2016: 47- Italics in original). Merleau-Ponty identifies ‘the experiencing ‘’self’’-with the bodily organism…’ (Abram 2016: 45), because ‘without this body… without any glimmer of sensory experience, there could be nothing to question or to know’ (Abram 2016: 45). Goodall’s experience may be less an abandonment of body-self than a merging of her body-self with ‘earth and trees and air’ (Goodall in Taylor 2010: 29), into a full sensual experience. The Cloud Appreciation Society’s (CAS) manifesto states that: ‘clouds are for dreamers and their contemplation benefits the soul’ (CAS website). This association with clouds and dreamers is nothing new. During Aristophanes’ play The Clouds (423BC), Socrates declares: ‘They are the Clouds of heaven, great goddesses for the lazy …’ (Aristophanes: online). It seems when people are in ‘contemplation’ (CAS website), while immersed in cloud, rain, or wind, they receive revelations: Goodall’s experience happened when the weather changed. Knight (2016) experienced similar moments on Dartmoor: ‘I was literally ‘cloud-walking’, surrounded by the breath of the dragon. I once sat down and tuned into the simulacra at Hound Tor, and words entered my head, as if the rocks were speaking’ (Knight 2016: 73- Italics in original). This can be compared with Keats’ journey up Ben Nevis: he arrived in a white-out, and faced a ‘revelation of how nothing is clearly revealed. What is a ‘thought’, he asks, but more of this mist? Turning himself inside-out, Keats makes the cloud around him a projection of his own mind. If the cloud has besieged him from above and below, he responds by claiming those clouds as vast mental space. Standing in the mist we are suddenly looking round at the great interior of Keats’s brain’ (Harris 2016: 246). For Keats, boundaries between himself and the external world around him have disappeared, much like Goodall’s experience of the self being absent. I did not experience my ‘self being absent’ during this research, mainly because, I confess: Sunday 5th August, 7pm, Glastonbury, sunny and warm, some cloud-cover. I’m realising how little time I have in my life for cloud-gazing.[1] However, I did experience feelings of non-separation. There are two examples, and both occurred during what could be considered bad weather: Friday 13th July, 3pm, Somerset Levels, raining. A raincloud is made of the same ‘stuff’ as water, which falls from it, soaks me, everything around, and flows into the ground. So what looks like a separate ‘thing’: a cloud, in fact is not separate at all. (Figure 1) Saturday 14th July, 8pm, Glastonbury Tor, bright and windy. I felt like walking up the Tor…and on the way we bumped into a few friends. They said it was windy up the Tor earlier (as it often is)-and I said ‘good I feel like being blown around a bit!’ It did the trick-one feels more alive in the wind, slightly out of control and like all the ‘stuck’ feelings are being swept away, disintegrating among the clouds. In the former example, I could see and feel how a cloud, which might be considered separate (from earth, myself), was in fact all-encompassing to everything around it. In the latter example, I felt how the self can be immersed in weather: my-body-self felt different after this experience. Ingold considers that: ‘To inhabit the open world… is to be immersed in the fluxes of the medium: in sunshine, rain, and wind’ (Ingold 2007: 30). This immersion happens predominantly in extremer weather. By overwhelming the senses, wind and rain can ‘drown out the perception of contact with the ground’ (Ingold 2010: 131), which is what happens to both Keats and Knight, as they become one with the surrounding cloud. In conclusion, I find myself envying those who can immerse themselves in cloud and weather, and find that absence of the self. I understand feelings of non-separation, and can see how it could happen, while I have not experienced it myself. If ‘clouds are for dreamers’ (CAS website), then I would like to dream more, and give myself more time to experience oneness with the clouds. Emotional reaction to clouds As inhabitants of Earth, humans are constantly subject to weather: ‘The experience of weather lies at the root of our moods and motivations’ (Ingold 2010: 122).[2] Van Gogh, who painted the picture on the front of my journal cover (Figure 2): A Wheatfield with Cypresses (1889), used emotion and mood in paintings of clouds. In this description of another of Van Gogh’s paintings, Starry Night (1889), Gedzelman (1990) could well be describing the former painting: ‘Everything seems almost to flow, bending or wavering… but still remaining clearly identifiable… the contorted and up-thrust mound-like hills… the undulating ground, clouds, and cypress…’ (Gedzelman 1990: 109). Ingold suggests that Starry Night is emotive ‘because it both resonates with our experience of what it feels like to be under stars and affords us the means to dwell upon it-perhaps to discover depths in this experience of which we would otherwise remain unaware’ (Ingold 2016: 220). Feasibly the same applies for A Wheatfield with Cypresses: the viewer, swept up in the flow of the clouds, experiences a depth of emotion unusual in every-day life. In short: I can ‘feel’ the clouds in the painting. This journal extract illustrates how I contemplate the painting whilst looking at the sky: Tuesday 26th June, Somerset Levels, 11 am, sunny and clear sky. First time in so long I’ve seen a clear blue sky with absolutely no clouds. Beautiful day, beautiful colour sky, but I am also aware that if it were like this all the time, how boring that would be- imagine A Wheatfield with Cypresses (Figure 2) with a clear blue sky instead of swirling clouds. It is easy, though, to miss clouds on sunny days, but the rainclouds will come, and heavy emotions can come with them. Harris indicates that ‘our thoughts are affected by the kind of weather we‘re in. Dark clouds are liable to engender gloomy feelings. The weather can be responsible not just for our own mood but for the mood of the entire town or country’ (Harris 2016: 14). Hunt (2018) would agree that the weather affects people’s moods. He journeyed to find the big winds of the world, and discovered that they can make people sick, and mad: ‘Not for nothing is the Mistral, which can rage for weeks on end in the south of France, known as the “wind of madness”‘ (Hunt 2018: online). He also encountered a German wind called Foehn, which affects locals (and eventually himself) ‘on a deeper, psychic level’ (Hunt 2018: online). Recording people’s stories, he said: ‘mostly people complained of stress; fretfulness; anxiety; nerves; irritability; angst; paranoia’ (Hunt 2018: online). When Van Gogh painted A Wheat Field with Cypresses in the south of France, had the Mistral ‘wind of madness’ (Hunt 2018: online) been blowing? Van Gogh is not the only artist to have been affected emotionally by the sky. Harris says that John Constable (1776-1837), famous for his cloud paintings, names the sky as ‘a feeling organ, but the sentiments are surely those of the perceiver’ (Harris 2016: 245). Is this true? The CAS manifesto says ‘We seek to remind people that clouds are expressions of the atmosphere’s moods, and can be read like those of a person’s countenance’ (CAS website). The society considers clouds to have their own moods and emotions, just as Constable suggests. Tilley (2004) understands how painter and subject feel one another: 'The painter sees the tree and the tree sees the painter, not because the trees have eyes, but because the trees affect, move the painter… In this sense the trees have agency and are not merely passive objects' (Tilley 2004: 18). Constable, CAS, and Tilley, all imply, then, that clouds have agency, emotions, and sentiments that affect people, just like meeting another person in a certain mood. Perhaps Van Gogh would agree. Monday 16th July, Wells, 4pm, pouring with rain. I resigned myself to living as part of a world where the weather has no regard for the people around. But is that true? The whole day was strange- people agitated, cross, insulting. People losing things. Everything that could go wrong, did! Someone even got arrested outside the Cathedral. A stormy day, indeed! That day I experienced how the weather affected people’s moods, and perhaps how clouds have agency, as Tilley (2004) suggests. Many times during this research I felt myself caught up in the mood of the weather: happy and energetic on sunny days, gloomy on rainy ones, and swept away by Van Gogh’s wave-clouds. I conclude that my emotions are most certainly affected by clouds and weather, and quite possibly I affect the clouds in return. Cloud images, stories and conversations If one accepts that clouds have agency, is it then possible to speak to and learn from them? One of my journal extracts describes a conversation with clouds. It was so clear, and yet unexpected: the images I saw in the clouds were a direct communication. Sunday 29th July, Glastonbury, 6pm, sunny/ cloudy, warm. I was thinking about my life and how I should live it- when suddenly a blue heart-shape appeared out of the cloud (Figure 3). It reminded me: I am loved… As I was about to go inside I looked up once more to see a giant turtle face gazing at me (Figure 4)… that’s when I knew for sure the clouds were talking to me: I already know my turtle spirit-animal very well. Attributing life, or agency, to the natural world has been named animism, which is ‘not a system of beliefs about the world but a way of being in it, characterized… by sensitivity and responsiveness to an environment that is always in flux’ (Ingold 2007: 31). Martin Heidegger (1993) suggests that ‘’’on the Earth’’ really means ‘’under the sky’’ also ‘’remaining before the divinities’’…’ (Heidegger 1993: 351). This primal oneness merges earth, sky, divinities and mortals, together in one, felt through being sensitive and responsive to the ever-changing environment. One of the main characteristics of clouds is that they are ‘always in flux’ (Ingold 2007: 31). Many cultures have cosmologies that relate clouds to divinities, including the above example of Aristophanes’ cloud-goddesses (Aristophanes: online). Harris attributes this cloud-divinity link to the fact that one cannot touch a cloud: ‘This elusiveness, combined with tremendous power, means that in almost every culture the weather has at some stage been thought divine’ (Harris 2016: 12). Harris continues: ‘The immateriality of weather has made it a potent means of figuring not only our gods but the most immaterial part of ourselves – our ‘spirits’ and thoughts... There was a strand of early Christian mythology that imagined Adam’s thoughts to have been fashioned directly from the clouds’ (Harris 2016: 12). The word inspire is related to spirit, and to breathing: the air; and so perhaps this is where the inspiration for mythologies and stories come from: the air itself, just as I received inspiration from the clouds that day. Some mythologies feature clouds and wind very heavily. The Native American Creek people tell that ‘Hesakitumesee, the Master of Breath… sends fog, wind, and other weather across the land, affecting the destiny of the people’ (Abram 2016: 228). Holy Wind in Dine culture ‘suffuses all of nature, and…grants life, movement, speech, and awareness to all beings. [It is] the means of communication between all beings and elements’ (Abram 1996: 30- Italics in original). The Lakota honour the four winds: ‘As messengers of the gods, the winds are the first powers to be addressed in any ceremony’ (Abram 1996: 229). It may be imperative to consider how winds, clouds, and weather are addressed and reacted to, because they affect people’s destiny and allow communication between all things. Knight (2016) mourns the loss, in the modern world, of seeing divinity in natural features: ‘nowadays a face in a rock is just a coincidental action of weathering, whereas it may once have been perceived as an ancestor or an element of tribal myth’ (Knight 2016: 5). He sees in simulacra faces, animals, and natural elements, which I saw many times during my cloud-gazing study (Figures 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7). Knight thinks ‘perhaps we need to recapture that primeval eye, that mode of perception that finds sermons in rocks…’ (Knight 2016: 31). Abram would agree that recapturing ones’ perception of invisible air is vital: ‘only as we begin to notice and to experience, once again, our immersion in the invisible air do we start to recall what it is to be fully part of this world’ (Abram 1996: 260). Perception is ‘a sort of silent conversation that I carry on with things, a continuous dialogue that unfolds far below my verbal awareness’ (Abram 1996: 52). My conversation with the clouds reflects this phenomenological, silent conversation. I conclude that mythologies and stories can be inspired by air, through images perceived and silent conversations taking place. Native American and other cultures honour and respect clouds and weather, because they are aware of how people are affected by the constant flux. I aim in future to consider my reactions to clouds and weather, because this is a two-way conversation. I would like to end with a sentiment from the CAS manifesto: ‘Look up, marvel at the ephemeral beauty, and always remember to live life with your head in the clouds!’ (CAS website). Conclusion This project explored the phenomenological effect of clouds on myself, using a Sky Journal to record my cloud-gazing experiences. Firstly I investigated how clouds create a sense of oneness with my surroundings, drawing on Goodall’s experience of absence-of-self; Ingold’s (2010) discussion of weather-immersion; Keats’ disruption of boundaries (in Harris 2016); and Knights’ (2016) experiences of receiving messages while immersed in weather. Secondly I considered how different clouds and weathers affect my emotions, again drawing on Ingold’s (2010) weather-work, as well as Van Gogh’s emotional paintings (in Gedzelman 1990), and Hunt’s (2018) exploration of extreme winds affecting people emotionally. Finally I discussed how story and mythology reflects clouds and weather, through images seen and conversations held between myself and clouds. I contemplated Harris’ (2016) views on Christian imagery, and Abram’s (1996) Native American cosmologies, to understand how people’s reactions to clouds affect them on a personal level. My research has led me to discover that I am more affected by clouds than I previously considered. I can imagine a sense of oneness with my surroundings, and I would like to give myself more time to explore this further. While I did not experience the merging self-with-weather, as Goodall and others have done, I understand more fully how non-separation is experienced. Another definite conclusion is that clouds and weather affect my mood, and the emotions of others around me. I am uncertain whether, as Tilley (2004) suggests, clouds have agency and can therefore also be affected by interaction with myself. Again, this is something that calls for extra research. Finally, I consider seeing certain images in the clouds as a direct communication between clouds and myself. I found that exceptionally inspirational. Other cultures are extremely careful in how they interact with clouds and weather: they watch and listen and reciprocate, and I would like to do more of the same. I agree with Abram (1996: 260) that through this exploration in air, I do feel more part of the world, more immersed and more listened-to in turn. My aim in future is to do as the CAS suggest, and live my life with my head in the clouds! [1] Harris would empathise: ‘I am the most amateur and faddish of weather watchers. I cannot sit looking at the sky for long without getting restless’ (Harris 2016: 19). [2] The English word ‘temper’ means both ‘mood’ and ‘weather’. Ingold says: ‘The fact that a whole suite of words derived from this common root refer interchangeably both to the characteristics of the weather and to human moods and motivations is sufficient proof that the two are not just analogous but fundamentally identical’ (Ingold 2010: 133).

0 Comments

I am proud to be a Companion of Chalice Well Gardens in Glastonbury, a place to wander, sit, contemplate and simply be.

Chalice Well is one of the best loved, most ancient wells in England. Pilgrims come to visit from all over the world, to drink its sacred waters and sit in its peaceful gardens. Last year I visited almost every month during the summer for the Full Moon music events held on the lawn, always a relaxed yet celebratory evening. And I have been to the Imbolc and Beltane meditations at the well itself, usually very popular events but beautifully done. Ark Redwood is the head gardener in the gardens, and he wrote (among others) a wonderful book called The Art of Mindful Gardening, which I read in raptures. The book takes you through the year, celebrating the seasons and giving mindfulness exercises to do while performing everyday gardening tasks. The photos below take you through the gardens, from the pool at the bottom, in the shape of Chalice Well with the two intertwining circles, up to the waterfall and the pool in which you can paddle or bathe, up to the drinking water fountain, through the abundant flowers to the well itself, a place of quiet contemplation, and up again to the top of the garden, with views of Glastonbury Tor. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed